Article 35A: THE BANE OF THE WEST PAKISTAN REFUGEES.. Part 2

| 11-Sep-2018 |

1. Introduction

In India, the concept of a “right to life” has been debated and dissected in all three wings of the government, yet we see that there is an institutional deprivation of this particular right to multitudes of people. Even with the existence of legal measures in place to ensure equality, there is an obvious lack of access to rights and opportunities for a multitude of people. We may attribute this to a number of factors, for example, vested political interests or the lack thereof, the oppression of a community to the extent that they do not have a voice, or lack of political representation. Often, in a country as vast as India, there are particular communities that become the victims of such political inadequacy, living in subhuman conditions and deprived of their basic human rights.

In 1981, the Supreme Court ruled that “The right to life includes the right to live with human dignity and all that goes along with it, namely, the bare necessaries of life such as adequate nutrition, clothing and shelter and facilities for reading, writing and expressing oneself in diverse forms, freely moving about and mixing and commingling with fellow human beings” (Francis Coralie Mullin v. The Union Territory of Delhi, 1981). In a country like India, the world’s largest democracy, it is a point to lament that there are a number of communities that do not have the access to this basic human right, even though they may be citizens of the country. In the context of this statement, I will argue that the community of West Pakistan Refugees is such a group of people, who have been denied these rights

.

1.1 - History of Jammu and Kashmir

In ancient times, the area of Jammu and Kashmir was a region where intellectualism flourished, and was rich with culture, music, and art, as it acted as a gateway into the Indian Peninsula. Many pilgrims and missionaries also passed through the area, and there is much documentation of the beauty and prosperity of the area. The people were either Hindu or Buddhist in the kingdom, as were the rulers until 1339. After this, the kingdom went into the hands of Shah Mir, who ruled under the name of Sultan Shamas-ud-din, and this Muslim rulership continued for 222 years (Dhar, 1984). According to Dhar, it was during this period of time that the religion of Islam was consolidated. From 1587 until the mid-1700s, the Mughals took over the region of Jammu and Kashmir. It is believed that until the rule of Shah Jahan, there was peace in the kingdom, with all religions living in harmony, but “Aurangezeb's reign was a signal for revolts and rebellions in several parts of the country. In distant parts of the empire commenced an era of lawlessness, anarchy and disorder. A reign of disorder also started in Kashmir. The Moghul Governors began to loot and plunder the people, and at the same time ruthlessly started a policy of religious bigotry and fanaticism.” (Dhar, 1984)

Persian ruler Nadir Shah took advantage of this chaos, and invaded the region, placing Ahmad Shah as a governing ruler of Kashmir. This was a period of bigotry and religious fanaticism, in which the people of the valley suffered on the whole, and the rulers targeted the Hindus, Bombas, and the Shia Muslims, especially in the Jhelum valley. As a revolt to these avaricious rulers, the people revolted and pleaded with the then ruler of Punjab, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, to help free them from these rulers who were terrorising the people. Though the Sikh rule, once established in 1819, was apathetic at best, the people were relieved to have done away with the Persians. In 1846, the Anglo-Sikh wars were fought, and after the loss of the Sikhs, the Dogra ruler of Jammu – Gulab Singh – took over the region.

The Dogra rule handed over their kingdom to the Dominion of India in 1947, Jammu and Kashmir became an official state of the sovereign Republic of India. Though these events seem clear on paper, there were a lot of discrepancies and misunderstandings involved in this process, which led to the eventual issue of the West Pakistan Refugees. In order to understand their current situation, therefore, we must also discuss these events that led to their subjugation.

1.2 - Partition of British India

The West Pakistan Refugees are a community of people who migrated to India in the wake of the partition in 1947, and have been living in the state of Jammu and Kashmir ever since. British India was partitioned on communal lines to create India and Pakistan in the year 1947, and this partition was supervised by the British, as well as the leaders from both sides. The partition used the concept of the ‘Two Nation Theory’ as its ideological basis, and was propounded by Mohammad Ali Jinnah in this argument for the partition of British India. The partition of the province of Bengal by Lord Curzon in 1905 had already laid the foundation for partition on a communal basis. Using the same framework, four provinces of the Indian subcontinent were to go to the newly formed nation of Pakistan – Western Punjab, Eastern Bengal, Sindh and the North-West Frontier Province.

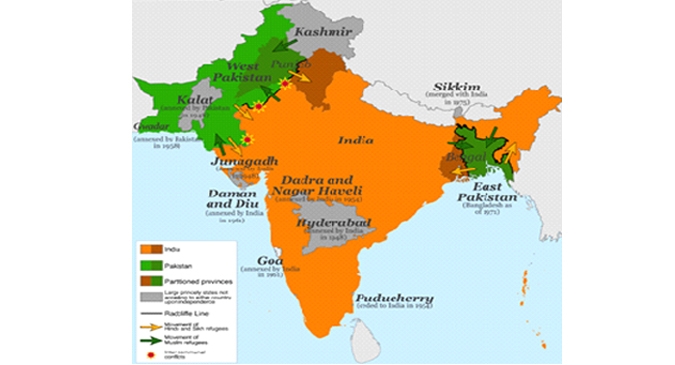

As we can see in Figure 1, Pakistan was divided into East Pakistan (made up of the province of East Bengal, now Bangladesh), and West Pakistan (made up of the provinces North-West Frontier, Sindh and West Punjab), which were the Muslim-dominant areas of the country. The princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, under Dogra king Raja Hari Singh, initially wanted to remain independent, but since this was not an option, it acceded to India via the Instrument of Accession on 26th October, 1947, for military aid and protection from the invasion by the citizens of the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan.

When India was partitioned in 1947, it was done so under the supervision of Lord Mountbatten and the line of partition itself was drawn by Sir Cyril Radcliffe, who was made the chairman of the Indian Boundary Committees. Sir Radcliffe had neither been to Asia before, nor had any geographical or demographic knowledge of the subcontinent. This was seen as positive at the time, assuming that it would ensure impartiality in the division (Pillalamarri, 2017). In retrospect, we see that his decision was uninformed and random, and led to the “largest migration in human history”. Mythreyee Ramesh states that this line brought about the massacre of over a million people, and has not stopped bleeding since 1947 (Ramesh, 2017). This means that the repercussions of this imbalanced partition have been multiplying since then, and the West Pakistan Refugees are simply one example of such repercussions.

Mohammad Ali Jinnah was the key proponent of the partition of British India, and claimed that it was necessary on the grounds that Hindus and Muslims cannot peacefully coexist in India after it becomes a free state. He strongly believed that forcing the two communities to live together would be the cause for bloodshed and violence, because historically they had always been on opposite sides of war, and viewed each other as enemies, even if they had put aside such differences to participate in the freedom struggle (Jinnah, 1940). He even had a contention with the Indian National Congress, which he believed was Hindu-dominated. The Congress refuted these claims, and tried to prevent the partition of the country at all costs, which they believed would cause more communal disharmony in the long run than it would prevent temporarily. Eventually, the country was partitioned, and the worst fears of the Congress and Mahatma Gandhi came alive.

As previously stated, the partition of British India was a mass exodus of people and has often been called the largest migration in known history. It is believed that around 14 million people were displaced from their homes, with Hindus and Sikhs fleeing Pakistan to come to India, and Muslims leaving India to go to the newly formed Pakistan. Such an exodus cannot be without violence, and though the numbers are unknown, a rumoured 200,000 to 2 million people are said to have died in the violence that succeeded the partition. Especially in Pakistan, which was to be a Muslim country, the Hindus and Sikhs were forced out by the masses, with bungalows burnt, women raped and entire families murdered in cold blood. This violence took place on both sides of the borders, with the masses completely polarised by the decisions of the leadership, giving in to emotionality and illogical rage. One of the most horrific instances is that of the “blood trains” – trains that were carrying refugees from one side to another that would be attacked by angry mobs midway, and by the time they reached the destination in the next country, only corpses remained on the trains (Doshi & Mehdi, 2017).

It was in the midst of all this chaos that the West Pakistan Refugees came to India. These people were the Hindus and Sikhs who, one day, found themselves on the wrong side of the border. Their families and neighbours were being massacred, and to avoid a similar fate, these people migrated to India. Of these evacuees, almost 80 to 90 per cent were from the Scheduled Castes and Other Backward Classes (Wadhwa Commitee, 2007), which meant that they did not even have much to begin with. The Radcliffe Award was announced on 17th August 1947, and was to be made effective immediately. Punjab was a huge province at the time, and was to be partitioned into East and West Punjab, with East Punjab getting 13 districts and 5 princely states, with 45 per cent of the population, 33 per cent of the area, and 31 percent of the former income of the province, and West Punjab got 16 districts, 55 per cent of the population, and 67 per cent of the area (Nargotra, A Study of West Pakistan Refugees in the State of Jammu and Kashmir, 2012, p. 80). Due to this, there was unchecked pandemonium, and riots began in West Punjab (the Pakistani side) in the districts of Lahore, Sialkot, Gujranwala and Shekupura. People migrated into India by any and all means possible, by cars, by air and rail, and many even crossed the border on foot. In reaction to violence on the Pakistani side of Punjab, the Hindus in India started retaliating against their Muslim neighbours, forcing an exodus from the Indian side as well. This massacre of communities on both sides of the border was one of the bloodiest holocausts that the world has seen.

Due to the nature of the exodus, a number of people came to India with a small amount of savings and no property, and many of these people had exhausted their savings simply by traveling to India. By the time that they reached the state of Jammu and Kashmir, therefore, they had no money, and were forced to settle in the land allotted to them by the Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, as well as the then-Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir – Sheikh Abdullah. This settlement of theirs will be elaborated on in the next chapter. In order to understand the current situation of the West Pakistan Refugees, we must also grasp the two legal provisions that keep them in their statelessness – Article 370 and Article 35A.

1.3 - Legal Provisions – Article 370 and Article 35A

Article 370 is an article found in part XXI of the Indian Constitution, under Temporary, Transitional and Special Provisions, and contains, according to its introductory text, “temporary provisions with respect to the State of Jammu and Kashmir.” According to Mohan Krishen Teng, the reason behind the creation of Article 370 lies in the fact that the state of Jammu and Kashmir was the only Muslim-majority state in the country, and therefore felt insecure about their security under a Hindu-majority government. The leaders of the National Conference, a political party of the region, refused to accept the integration followed the signature of the Instrument of Accession, instead asking for more autonomy within the government of India. They also accused certain Congress leaders of favouring the Dogra rulers and ignoring the demands of the Muslim-majority population of the state. They claimed that the document that had been signed was subject to their approval, and that “The future Constitution of the State and the constitutional relations between the State and the future federal organization of India would be determined by fresh agreements between the Interim Government and the Government of India.” (Teng, 1990, p. 32)

After a series of debates and discussions, as well as a smear campaign by Sheikh Abdullah on the Maharaja Hari Singh, who he believed represented the autocratic Hindu rulership of India, Abdullah threatened to align with Pakistan, who had been promising the state an autonomous status, with only certain topics like defence and foreign policy under the central control. After a round of heated debates, in which the National Conference leaders tried to establish complete autonomy of the state of Kashmir at the Delhi Conference with the Interim Government and the Constituent Assembly, an agreement was reached. The article, originally Article 306-A, was to be drafted by the Diwan of Maharaja Hari Singh, Gopalaswami Ayyangar, and supervised by the National Conference leaders (Teng, 1990, p. 46). A series of drafts were passed back and forth between the two sides, and finally an agreement was reached on the contents of Article 306-A (now 370) of the Indian Constitution. This was to be a temporary provision, as the state of Jammu and Kashmir was in a situation of both internal and external conflict and was, therefore, rendered unable to elect a Constituent Assembly at the time. It was assumed that with the creation of the Constitution for the state, the article would lose relevance and eventually be scrapped (Teng, 1990, p. 48).

After the final revision of the Constitution of India, Article 306-A was made into Article 370, and it came into force along with the rest of the Constitution on 26th January, 1950. The article limited the powers of the Central Government in the state to three powers under the Union List – military and defence, communications, and foreign policy. The state of Jammu and Kashmir was to have their own constitution, similar to other princely states like Saurashtra and Travancore. Though the latter two did not go through with the adoption of a state constitution, the state of Jammu and Kashmir did. Therefore, we can infer that the state of Jammu and Kashmir was in no way given special, or even separate status in the Union of India.

When we discuss Article 35A, we must also understand the history behind this particular provision. Under the government of Raja Hari Singh, there were four classes of citizen – the first two classes (class I and II) were those who had been inherently living in the state and were long-standing citizens of the state, that is, natural citizens. The second two classes (class III and IV) were those who were new to the state, and had been living in the state for a period of time, and therefore were granted citizenship under the concept of naturalisation. In the creation of Article 35A, the provision for naturalised citizens was removed, and only the one of natural citizens remained. Therefore, this is the article that establishes the “Permanent Resident” requirement in the administration of the state.

According to K. L. Bhatia, “Article 35A was neither a part of the draft Constitution nor a part of the adopted and enacted text of the Constitution of India. This Article was an addition to the Fundamental Rights (Part III) of the Constitution by a Presidential Order, viz., Constitutional (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 1954.” The article is also not placed in the body of the constitution, but rather in the appendix of the Constitution. It is under section (4) (j) of the Presidential Order.

The text of the article reads:

“Saving of laws with respect to permanent residents and their rights. — Notwithstanding anything contained in this Constitution, no existing law in force in the State of Jammu and Kashmir, and no law hereafter enacted by the Legislature of the State:

(a) defining the classes of persons who are, or shall be, permanent residents of the State of Jammu and Kashmir; or

(b) conferring on such permanent residents any special rights and privileges or imposing upon other persons any restrictions as respects—

(i) employment under the State Government;

(ii) acquisition of immovable property in the State;

(iii) settlement in the State; or

(iv) right to scholarships and such other forms of aid as the State Government may provide,

shall be void on the ground that it is inconsistent with or takes away or abridges any rights conferred on the other citizens of India by any provision of this part.” (Government of India, 1950)

In the context of this article, two very pertinent questions emerge. Can the President of India, completely ignoring the provisions of Article 368, simply add an article to the Constitution by Presidential Order? This would not only be a blatant disregard for the concept of separation of powers, but would also be a blow to the final power of the Parliament when it comes to legislation. The second question that this article begs is, can any article take away the Fundamental Rights of a citizen of India, especially the right to life? Any article that takes away the rights of people in a free country is a legal loophole, and can be taken advantage of in order to deride the democracy of a nation. Though the legal justification is provided to this article as under Article 370(1)(c) and Article 370(1)(d), we must look at the implications of such an article and its subtle draconian nature (Kaul & Sagar, 2017, p. 1), especially since this legal justification is flawed.

In the next chapter, the application of this Article on the lives of the West Pakistan Refugees will be discussed, along with the condition of the community in current times.

References

Dhar, L. N. (1984, June). An Outline of the History of Jammu and Kashmir. Retrieved from Kashmiri Overseas Association: http://www.koausa.org/Crown/history.html

Doshi, V., & Mehdi, N. (2017, August 14). Partition of India: 70 years later, survivors recall the horrors of India-Pakistan partition. Retrieved from The Washington Post: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia-pacific/70-years-later-survivors-recall-the-horrors-of-india-pakistan-partition/2017/08/14/3b8c58e4-7de9-11e7-9026-4a0a64977c92_story.html?utm_term=.cda3ffce280f

Francis Coralie Mullin v. The Union Territory of Delhi, 1981 AIR 746, 1981 SCR (2) 516 (The Supreme Court of India January 13, 1981).

Jinnah, M. A. (1940). Speech. Lahore, Punjab, British India.

Kaul, J., & Sagar, D. (2017). Article 35A: Face the Facts. New Delhi: Jammu and Kashmir Studies Centre.

Nargotra, S. (2012). A Study of West Pakistan Refugees in the State of Jammu and Kashmir. In R. Chowdary, Border and People - an Interface (pp. 79-110). Centre for Dialogue and Reconciliation.

Pillalamarri, A. (2017, August 19). 70 Years of the Radcliffe Line: Understanding the Story of Indian Partition. Retrieved from The Diplomat: https://thediplomat.com/2017/08/70-years-of-the-radcliffe-line-understanding-the-story-of-indian-partition/

Ramesh, M. (2017, August 14). Did Radcliffe Regret the ‘Bloody’ Line He Drew Dividing Indo-Pak? Retrieved from The Quint: https://www.thequint.com/news/india/partition-of-india-pakistan-cyril-radcliffe-line

Teng, M. K. (1990). Kashmir Article 370. New Delhi: Anmol Publications.

Wadhwa Commitee. (2007). Report of the Committee Constituted Vide Government Order No. Rev/Rehab/151 of 2007 dated 09.05.2007 for looking into the demands and problems of Displaced Persons. New Delhi.

2. West Pakistan Refugees – A Study

2.1 - Jammu and Kashmir – A Description of the Field

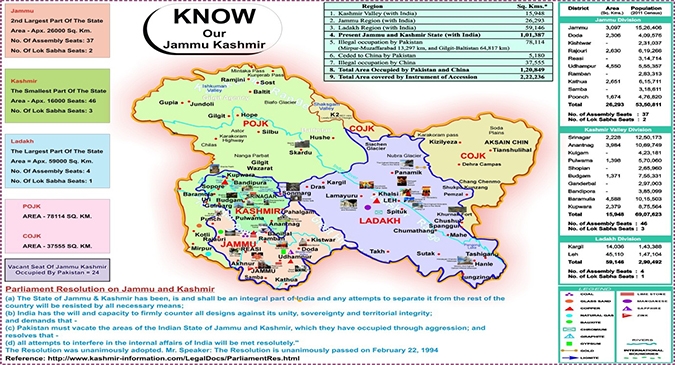

Jammu and Kashmir is the northern-most state of India, and is often referred to as the “crown of India,” due to its strategic importance as well as its natural beauty and resources. It was a part of the original Silk Route from China and was well connected to many other countries in the world. It is bordered by Pakistan to the West, China to the East and the Indian states of Himachal Pradesh and Punjab to the South. Due to its geographical value, it is a disputed territory between India and Pakistan, and large sections of the state have been illegally occupied by Pakistan and China. To the West, Pakistan holds Mirpur and Muzaffarabad (13,297 km²) and the Gilgit-Baltistan area in the North-West (64,817 km²). It has also ceded 5,180 km² of the Shaksgam Valley to China, and China has illegally occupied 37,555 km² of the Aksai Chin region.

Figure 2 is a depiction of the area of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, including the regions that are illegally occupied. The geography of the state is mainly characteristic of that of the Western Himalayan region, and is made up of seven zones. “From southwest to northeast those zones consist of the plains, the foothills, the Pir Panjal Range, the Vale of Kashmir, the Great Himalayas zone, the upper Indus River valley, and the Karakoram Range.” (Akhtar & Kirk, 2018). The Jammu region mainly consists of the plains, where the government is conducted in the winter, and Srinagar, in the Kashmir Valley, is the summer capital of the region. The electoral distribution and region-wise population is depicted in Figure 2.

Demographically, the state of Jammu and Kashmir has a Muslim majority, but is a mixing-pot of cultures and religions, such as Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists and also various tribes (Akhtar & Kirk, 2018). A variety of languages are also spoken, and there are many sub-cultures among the religions in the state. For example, the Muslims of the state can be further categorised into Kashmiri Muslims, Bakerwals, Gujjars and Dogras, while the Hindus can be largely categorised into Brahmins, Jats, Dogras, Paharis, whereas the Ladakhis are majorly Buddhist (Department of Tourism, Jammu and Kashmir, n.d.). According to the 2011 Census, there are 68.31% Muslims, 28.44% Hindus, 1.87% Sikhs and minorities of Jains and Buddhists.

2.2 - History of the West Pakistan Refugees and their Migration

As mentioned earlier, the West Pakistan Refugees were a part of the population exchange that took place during the partition of British India, and were mainly from Western Punjab province of Pakistan. Though a lot of these West Punjabis migrated to East Punjab, in the panic of the communal unrest in the provinces of West Punjab, there was a section of these people who came into India through Jammu and Kashmir, though not all chose to settle there. According to an investigation carried out by the Wadhwa Committee in 2007, they largely settled in 3 districts of Jammu and Kashmir – Kathua, Rajouri and Jammu (Wadhwa Commitee, 2007). In the same report, the committee states that these communities now live in the districts of Jammu, Katwa and Samba today.

In establishing the identity and origins of the West Pakistan Refugees, it is important to note that these people were mainly from the Scheduled Castes. Their arrival in India was already from a disadvantage due to their caste. Many of them walked, with bleeding feet, from the Sialkot district into the state of Jammu and Kashmir, fleeing violence and conflict. They were forced to cross mountains and barren land by foot, without food or water, and many died of illness and starvation, others of exhaustion.

Seema Nargotra posits four possible reasons for their settlement specifically in the state of Jammu and Kashmir (Nargotra, A Study of West Pakistan Refugees in the State of Jammu and Kashmir, 2012, p. 83):

(i) The physical proximity of Jammu to their villages. Most of the West Pakistan Refugees came from the Sialkot district, from where the cities of Gurdaspur and Amristar in Punjab were 98 and 92 kilometres respectively, while Jammu was only 38 kilometres from them. We must keep in mind that most of these people came into the country by foot, and therefore chose the closest place to settle.

(ii) Since these refugees were Hindu, they believed that their entry would be granted with ease through Jammu and Kashmir, since it was ruled by a Hindu king. Maharaja Hari Singh heard of the communal violence at the borders and instructed his army to allow Hindu refugees in, to prevent more bloodshed.

(iii) Punjab was the regular route used to cross the border, and many of the plunderers and rioters knew this. The villagers heard rumours of people waiting near the border to attack them, and chose to take an alternate route.

(iv) Since these people came into India as refugees, they felt more secure coming to Jammu and Kashmir, where many of them had relatives or friends. Another point that we must remember is that, in most cases, these people fled their homes with nothing but a small amount of money and possibly a few clothes. Therefore, for them, stability and security were key, and they would prefer to settle in a familiar place.

From the above reasons, we may infer that these people simply fled their homes in panic, and could not even imagine that their futures would be the way that they are. Now that we have the privilege of retrospect, we may say that this decision to come to the state of Jammu and Kashmir was a huge error on the part of the West Pakistan Refugees.

In an interview with a respondent, they informed the researcher that once they came to Jammu, some of them realised that, being a separate princely state, the kingdom had its own laws for a “state subject”, they attempted to migrate South, towards Punjab. By this time, Sheikh Abdullah had established his power as a prominent political leader, and along with Nehru, he asked these refugees to remain in the border villages. He stated that he would allow them to occupy the evacuee properties (EP) as well as some Government land from the border villages. He also promised to eventually make them state subjects (the equivalent of giving them a certificate of Permanent Residency). After his death, none of these promises were carried out, and according to the respondent, they still remain in the situation that they were in 71 years ago.

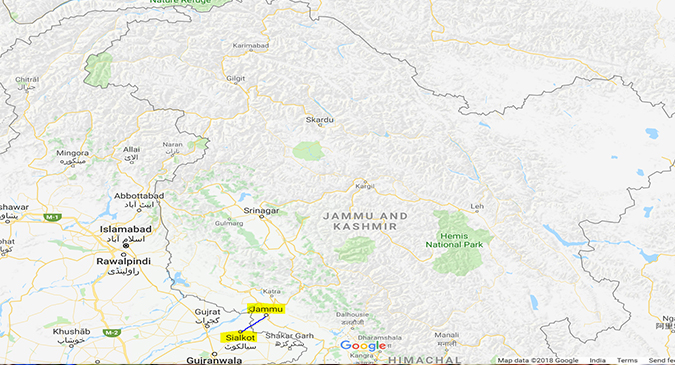

Figure 3

Figure 3 is a map of the region of Jammu and Kashmir, as well as the bordering regions of Pakistan, to give us an idea of the situation during partition, as well as the condition today. The blue line is to understand the tentative route that the refugees took during the exodus, as well as their actual physical proximity to the district of Jammu as compared to that of Punjab, which is much further south, and would have been an ordeal to reach for these evacuees.

Now that we have understood the historical factors in their migration to Jammu, we must also get a general idea of their current socio-economic condition as well as their political participation.

2.3 - Socio-economic condition of the West Pakistan Refugees

Figure 4

In the above map (Figure 4), we see highlighted the regions of interest. The West Pakistan refugees came mainly from the Sialkot district of West Punjab, migrating from villages like “Buur, Beli Ghagwal, Pul Bajua, Sandle Chak, Khoje Chak, Seed Mial (near Khoje Chak).” (Nargotra, A Study of West Pakistan Refugees in the State of Jammu and Kashmir, 2012). According to the Wadhwa Committee, 5764 families migrated into India during the partition, consisting of 47,215 people in total. The committee further states that no land was actually allotted to these refugees, but they were allowed to occupy 12 acres of Khushki land (“dry” land or unirrigated land), as well as 8 acres of Aabi (irrigated) land. Since this land is a part of the plains, it is heavily dependent on rainfall and seasonal rivers. Therefore, they have around 46,466 kanals of state land and evacuee property that they occupy as of 2007. (Wadhwa Commitee, 2007). Today, according to the records of the Office of the West Pakistani Refugee Action Committee, as attached in Appendix A, there are a total of 19,960 families, spread out in the regions of R.S Pura, Samba, Jammu, Akhnoor and Kathua primarily, as well as some other villages. This is depicted in Table 1. It is important to note, here, that the government did not bother to establish any sort of documentation of these West Pakistan Refugees. This is uncharacteristic of states which are on the borders, because the border villages are of strategic importance, and must have tight security. States like Uttarakhand and Punjab maintain strict records of these border-dwellers. Thus, this negligence of the state is not only appalling from a human rights perspective, but also from the angle of national security.

Table 1

In terms of the social composition of these refugees, as per the studies conducted by Nargotra, 80 per cent are of the Scheduled Castes, 10 per cent are Other Backward Classes and only 10 per cent belong to the General Category (Nargotra, A Study of West Pakistan Refugees in the State of Jammu and Kashmir, 2012, p. 96). Most of the localities they reside in have limited or no access to water, land and aid; attempts to give employment to these people have been half-hearted and not implemented; due to the lack of a Permanent Resident Certificate, children have had difficulty in enrolment, due to inability to pay school fees (Basavapatna, 2015, p. 57). Information gathered from the field also showed that most of these people live in kaccha (temporary) huts, and their livelihood is based on daily wage labour and being employed as informal domestic helpers.

2.4 - Hypothesis

Given the situation of the West Pakistan Refugees, as well as the exploitative nature of Article 35A, the researcher’s hypothesis will be that Article 35A has violated the basic human rights of the West Pakistan Refugees. The researcher has chosen this particular hypothesis in order to personally understand the limitations that Article 35A places upon the non-Permanent Resident Certificate holders of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. The researcher also hopes that this paper will act as a base for further academic research and discourse on the matter, as it is one of the ways that the topic will generate interest. The researcher hopes that such an interest will eventually translate into political will or a judicial decision, which will be the first step towards solving the problems of these people.

2.5 - Research Methodology

In order to understand and study this problem fully, the researcher chose to use a qualitative analysis. In the researcher’s opinion, in such a case, statistical data would only provide an answer to the “what” of the problem, where as a qualitative research would be more effective in answering the “why” and “how”. The researcher also chose to use an open-ended questionnaire, and in order to get a more in-depth understanding, conducted three interviews with experts and relevant personalities. In order to collect primary data, the researcher spent four days in Jammu, where she met with members of the West Pakistan Refugee community as well as the West Pakistan Refugee Action Committee and its leaders.

The first method used was the questionnaire, which is attached as Appendix B, and was a mixed questionnaire, containing both, open-ended and close-ended questions. The sample size of the questionnaire was 100 respondents, and was administered by “random sampling”, but the researcher encountered certain limitations in the administration. The first limitation encountered was that numerous respondents were illiterate, and therefore unable to write the answers to the questionnaires themselves. Another limitation was that these people were wary of filling any documents, and according to them, they did not want to risk losing the little that they had by putting their name on something unknowingly. Due to this, the researcher had to verbally ask the questions to the respondents and fill the questionnaires on their behalf.

In answering the questions, the community of West Pakistan Refugees were more than willing to talk about their problems. The researcher got a satisfactory understanding of the issues plaguing these people, but due to emotional aggravation, some of the stories that the respondents recounted could have been exaggerated for effect. That being said, the respondents seemed otherwise honest, and relevant information that was relayed to the researcher.

In addition to the questionnaire, the researcher also used interviews as a primary source of data. The researcher conducted four interviews with the following subjects – Dr. Seema Nargotra – a professor of Law from the University of Jammu; Daya Sagar – an author and expert on the constitutional provisions of Jammu and Kashmir; Labha Ram Gandhi – the President of the ‘West Pakistani Refugee Action Committee of 1947’; Dinesh Malhotra – a senior correspondent at the Tribune newspaper. The interviews provided an expert’s perspective to the issues raised by the respondents of the questionnaire, and were less subject to emotional bias.

The researcher also visited one of the villages of the West Pakistan refugees, known as Chak Jaimal. The village is located in the Samba region, around 8 kilometres from the Indian border with Pakistan, and has around 20 families. Some photographs of the village and the condition of living of these people are attached in Appendix C.

The researcher also made use of primary and secondary sources of literature, which are discussed under the next subtopic.

2.6 - Literature review

The West Pakistan Refugees are a community in India who have been ignored and marginalised for the better part of 70 years. They are a community who, due to the lack of Permanent Resident Certificates in the state of Jammu and Kashmir, have retained the status of “refugee” even though they are citizens of the Republic of India. Due to the general lack of awareness or concern for their situation, there has also been a vacuum of information in academic discourse about this community. The researcher’s data collection was also limited to the sample size of the questionnaire and the village, since, due to constraints of time and resources, it was not possible to visit all the villages of the community.

For the sake of convenience, the researcher will bifurcate the data collected into primary and secondary data sources. In terms of primary data, the researcher has made use of the Constitution of India, the Constitution of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, various committee reports on the issue of West Pakistan Refugees, petitions and documentation of the ‘West Pakistani Refugee Action Committee of 1947’, government data and the interviews conducted.

The Constitution of India enumerates the provisions of Article 370 as well as Article 35A, of which the latter is placed in the annexure of the document, by a Presidential Order. This lets us question the constitutional validity of the article and is open to interpretation. The researcher has largely referred to Article 368, Article 370 and Article 35A. (Government of India, 1950). The Constitution of the state of Jammu and Kashmir also gives us an idea of the requirements for the provision of “state subject” or the clause of Permanent Residency. The researcher has specifically referred to Part III of the document, which discusses the issue of “Permanent Residents” (The Government of Jammu and Kashmir, 1957).

The researcher has also made use of the Wadhwa Committee Report of 2007, which was a study undertaken on displaced persons in the state. This report enumerates the details of the demands made by the West Pakistan Refugees, as well as gives an overview of their condition. It is limited due to the lack of government data and acknowledgement of the mistreatment of these people (Wadhwa Commitee, 2007). The researcher has also referred to the report of the Joint Parliamentary Committee in 2014, which is a more detailed document and is inclusive of the replies from the incumbent Government of India, acknowledging that affirmative action must be taken in order to alleviate the misfortune of this community. The report also enumerates comprehensive recommendations for the West Pakistan Refugees (Joint Parliamentary Committee, 2014).

In terms of primary data, the documentation of refugees undertaken by the ‘West Pakistani Refugee Action Committee of 1947’ has also been informative. It has helped the researcher with specific numbers of the refugees, as well as their residence, their conditions and their demands. The researcher has attached the relevant documents, letters or petitions as appendices.

The interviews conducted gave the researcher an expert’s understanding of the situation of the West Pakistan Refugees. The interview with Dr. Nargotra was an insight into the legal nuances of the issue, but a limitation that the researcher encountered was that the interview was taken before the field study, due to which there were certain questions that remained unanswered (Nargotra, 35A and the West Pakistan Refugees, 2017). The second interview was with the author, Daya Sagar, which talked about the activities of the West Pakistan Refugees as well as the role of the government in the only state in India with a separate constitution. He also discussed the misuse of this status by the government and how they use it to exploit the disadvantaged masses and discriminate against non-‘Permanent Resident Certificate’ holders. A limitation was that the interviewee referred to certain documents which the researcher was unable to verify (Sagar, 2017). Another interview conducted was with Labha Ram Gandhi, who acted as the voice of the community of West Pakistan Refugees. In this interview, the researcher got a first-hand recollection of the worsening situation of this community, as well as a count of the activities and attempts undertaken by the West Pakistan Refugee Action Committee to get rid of the oppressive weight of Article 35A, including petitions to the Supreme Court of India (WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 871 OF 2015, 2016) and letters to important political leaders, of which the relevant ones are attaches as appendices (Gandhi, 2017).

The researcher has also referred to various court cases, such as Bachan Lal Kalgotra vs the State of Jammu and Kashmir, in which the Supreme Court took up the case of 35A but made no actual judgement, instead recommending legislative recourse to the government of Jammu and Kashmir. (Bachan Lal Kalgotra vs State of Jammu & Kashmir and Others, 1987).

The secondary sources that the researcher has used are the articles, chapters and books written on the issue of 35A in relation to the West Pakistan Refugees. The first source is a chapter from the book by Rekha Chowdhury, Borders and People – an Interface, and is written by Seema Nargotra. The chapter discusses the issues of the West Pakistan Refugees in detail and starts by tracing their history. It goes on to discuss the socioeconomic situation in detail. It also talks about the legal provisions of the governments, both Centre and State, that reinforce the disability of these people, such as the provisions of the Jammu and Kashmir constitution under Part III (previously mentioned in the paragraph on primary data) or the notifications made by the Maharaja Hari Singh in 1927 on the topic of “state subject”. It then talks about the initiatives taken by the government in order to deal with this issue, such as the creation of the Wadhwa Committee in 2007, or the All-Party Meeting held in May of the same year. Nargotra also discusses the interaction of the ‘West Pakistan Refugee Action Committee of 1947’ with the government and the political parties. She then gives a detailed break-up of the problems faced by these people, such as education, employment, land ownership and so on, and then concludes with suggestions and solutions to the problem. The only limitation in this comprehensive piece is that the data collected is from 2012, and therefore 6 years of data is not accessible (Nargotra, A Study of West Pakistan Refugees in the State of Jammu and Kashmir, 2012).

Another document that the researcher has referred to is the book by Jawaharlal Kaul and Daya Sagar, known as Article 35A: Face the Facts, which discusses all the details of article 35A in the state of Jammu and Kashmir. The book discusses four general topics – the actual facts of Article 35A, the volatile anger of the Kashmir valley leaders on the topic, and the constitutionality of the article. Though the book enumerates details about the politics and events surrounding this article, it lacks references, which could take away from the credibility of the book.

In the book, the State of being Stateless, the chapter known as The Remains of Partition? By Sahana Basavapatna discusses, in brief, the case of the West Pakistan Refugees, as being those people who are citizens of a country, yet live in the same conditions as those who are stateless. The data is limited but the insights and suggestions are of value in this particular source (Basavapatna, 2015).

The researcher has also referred to various articles from online newspapers, such as The Washington Post (Doshi & Mehdi, 2017), the Hindu (Yasir, 2018) and The Guardian (Safi, 2017) which discuss different issues regarding West Pakistan Refugees and Article 35A.

In conclusion, we see a lack of detailed analysis of this topic, and most of the information provided is generic, superficial and overlapping. This is one of the reasons that the researcher believed it was a pertinent topic to research, as it required more recognition. In the next chapter, the researcher will collate and analyse the data collected in the field.

References

Akhtar, R., & Kirk, W. (2018, February 2). Jammu and Kashmir. Retrieved February 15, 2018, from Encyclopaedia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/place/Jammu-and-Kashmir

Bachan Lal Kalgotra vs State of Jammu & Kashmir and Others, 1987 AIR 1169, 1987 SCR (2) 369 (Supreme Court of India February 20, 1987).

Basavapatna, S. (2015). The Remains of Partition? The Citizenship Question for Stateless Hindus in India. In P. Banerjee, A. B. Chaudhury, & A. Ghosh, the STATE of being STATELESS (pp. 52-74). Orient Blackswan.

Department of Tourism, Jammu and Kashmir. (n.d.). Ethnic Groups. Retrieved February 15, 2018, from Department of Tourism, Jammu and Kashmir: http://www.jktourism.org/index.php/cultural/ethnic-groups

Dhar, L. N. (1984, June). An Outline of the History of Jammu and Kashmir. Retrieved from Kashmiri Overseas Association: http://www.koausa.org/Crown/history.html

Doshi, V., & Mehdi, N. (2017, August 14). Partition of India: 70 years later, survivors recall the horrors of India-Pakistan partition. Retrieved from The Washington Post: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia-pacific/70-years-later-survivors-recall-the-horrors-of-india-pakistan-partition/2017/08/14/3b8c58e4-7de9-11e7-9026-4a0a64977c92_story.html?utm_term=.cda3ffce280f

Francis Coralie Mullin v. The Union Territory of Delhi, 1981 AIR 746, 1981 SCR (2) 516 (The Supreme Court of India January 13, 1981).

Gandhi, L. R. (2017, December 27). Views of The President of WPR Action Committee of 1947. (S. Rao, Interviewer)

Government of India. (1950, January 26). The Constitution of India. Retrieved February 9, 2018, from Indian Kanoon: www.indiankanoon.org

Jinnah, M. A. (1940). Speech. Lahore, Punjab, British India.

Joint Parliamentary Committee. (2014). ONE HUNDRED EIGHTY THIRD REPORT: Problems being faced by refugees and displaced persons in J&K. New Delhi: Rajya Sabha Secretariat.

Kaul, J., & Sagar, D. (2017). Article 35A: Face the Facts. New Delhi: Jammu and Kashmir Studies Centre.

Nargotra, S. (2012). A Study of West Pakistan Refugees in the State of Jammu and Kashmir. In R. Chowdary, Border and People - an Interface (pp. 79-110). Centre for Dialogue and Reconciliation.

Nargotra, S. (2017, December 26). 35A and the West Pakistan Refugees. (S. Rao, Interviewer)

Noorani, A. G. (2015, August 13). Article 35A is beyond challenge. Retrieved from Greater Kashmir: http://www.greaterkashmir.com/news/opinion/article-35a-is-beyond-challenge/194167.html

Pillalamarri, A. (2017, August 19). 70 Years of the Radcliffe Line: Understanding the Story of Indian Partition. Retrieved from The Diplomat: https://thediplomat.com/2017/08/70-years-of-the-radcliffe-line-understanding-the-story-of-indian-partition/

Ramesh, M. (2017, August 14). Did Radcliffe Regret the ‘Bloody’ Line He Drew Dividing Indo-Pak? Retrieved from The Quint: https://www.thequint.com/news/india/partition-of-india-pakistan-cyril-radcliffe-line

Safi, M. (2017, August 14). In limbo for 70 years, stateless West Pakistani families bear scars of partition. Retrieved December 22, 2017, from The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/aug/14/west-pakistani-families-partition-anniversary-india-1947

Sagar, D. (2017, December 29). Political Scenario in J&K and the West Pakistan Refugees. (S. Rao, Interviewer)

Sharma, G. D. (2004). JAMMU AND KASHMIR PERMANENT RESIDENTS (DISQUALIFICATION) BILL, 2004 IS UNCONSTITUTIONAL. Supreme Court Cases - CONSTITUTIONAL LAW. Retrieved February 12, 2018, from Eastern Book Company: http://www.ebc-india.com/lawyer/articles/2004v6a3.htm

Teng, M. K. (1990). Kashmir Article 370. New Delhi: Anmol Publications.

The Government of Jammu and Kashmir. (1957, January 26). The Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir. Retrieved February 11, 2018, from Jammu and Kashmir Legislative Assembly: http://jklegislativeassembly.nic.in/Costitution_of_J&K.pdf

United Nations. (2018, January 16). Human Rights. Retrieved from United Nations: http://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/human-rights/

Wadhwa Commitee. (2007). Report of the Committee Constituted Vide Government Order No. Rev/Rehab/151 of 2007 dated 09.05.2007 for looking into the demands and problems of Displaced Persons. New Delhi.

WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 871 OF 2015, 871/2015 (Supreme Court of India 2016).

Yasir, S. (2018, February 8). Article 35A: BJP calls for repeal while Kashmir govt pays high-priced lawyers to defend it in Supreme Court. Retrieved February 10, 2018, from The Hindu: http://www.firstpost.com/india/article-35a-bjp-calls-for-repeal-while-kashmir-govt-pays-high-priced-lawyers-to-defend-it-in-supreme-court-4342363.html

continue part 3