Properties and possessions of Mohammad Ali Jinnah

| 27-Apr-2020 |

Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the Quaid-e-Azam of Pakistan was deeply attached to his possessions and wealth that he owned, apart from his strong ambitions of being a great leader. However, when Jinnah eventually took off for his about to be born Pakistan, he left his house, properties, and personal affairs in an uncharacteristic mess. Everything that belonged to him, whether the house, servants, or his wealth had to be left behind for his lawyer to deal with.

After India-Pakistan separation, while leaving Delhi for the last time on 7th August 1947, Jinnah had remarked enigmatically, 'That's the end of that;' that this was the last time he would be seeing Delhi. Despite such assertions, his two houses in two big cities, one in the Malabar Hill of Mumbai and the other on the Aurangzeb Road in Delhi kept Jinnah tied to India.

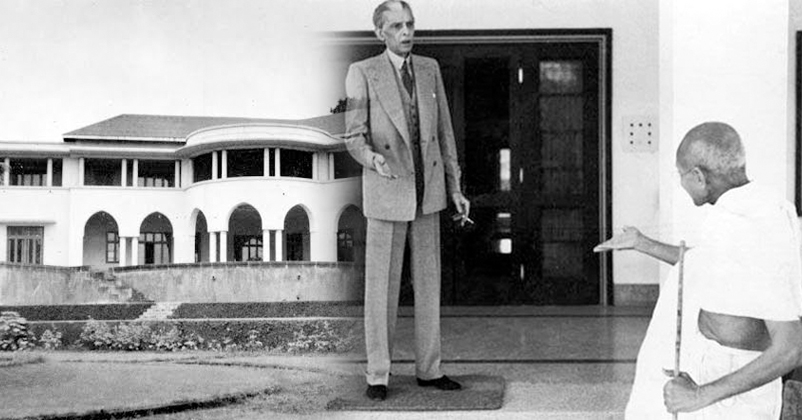

The Mumbai house, which Jinnah dearly loved, where the Jinnahs mostly lived while their marriage lasted, with their only child and dogs and cats and, of course, servants, was initially left undisturbed by the Government of India out of consideration for him. The sprawling white mansion spread over two-and-a-half acres on Mumbai’s Malabar Hill, with its pointed arches and imposing columns, was once so famed for its marbled splendor that hordes of admiring tourists would come up to its guarded gates to try and catch a glimpse of it from afar. At first, the house was not requisitioned like other evacuee property, out of respect for him but later prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru faced so much embarrassment on account of this courtesy from his parliamentary opponents that he finally instructed that the government could no longer keep his property lying vacant. .

How Jinnah’s two houses in Mumbai and Delhi kept him tied to India and what was done with the properties after Jinnah left for Pakistan!

As there was immense pressure on the government on this score, Prime Minister Nehru called up India's high commissioner in Karachi, Sri Prakasa, to say that the government was under pressure to requisition the house. He instructed Sri Prakasa to see Jinnah, find out his wishes, and the rent he would like to have. Jinnah was taken aback with Nehru's message and told Sri Prakasa, 'Tell Jawaharlal not to break my heart. I have built it brick by brick. Who can live in a house like that? What fine verandahs! It is a small house fit only for a small European family or a refined Indian prince. You do not know how I love Bombay. I still look forward to going back there.'

'Really Mr. Jinnah', Sri Prakasa said, 'You desire to go back to Bombay? I know how much Bombay owes to you and your great services to the city. May I tell the Prime Minister that you want to go back there?' He replied: 'Yes, you may.' The high commissioner informed Prime Minister Nehru accordingly and the house remained as it was. However, after some months Nehru again spoke to the high commissioner saying that the government was being embarrassed by the adverse remarks on the house being left untouched. It would have to be requisitioned. The prime minister asked Sri Prakasa to inquire from Jinnah the rent he would like to have.

Jinnah, who by then was unwell and recuperating in Quetta/ Ziarat in Balochistan, said he had been offered Rs 3,000 a month and hoped his wishes regarding the nature of the tenant would be respected. The British deputy high commissioner rented the house for Rs 3,000. He had a small family and so Jinnah's wishes were fulfilled. Another condition for the lease was that should Jinnah ever want the house for himself, the tenant would have to vacate it immediately.

For the Delhi house, Jinnah managed to negotiate its sale but there were complications since it had become evacuee property and so the sale could not be registered. Jinnah was very upset about this and even complained to the Indian high commissioner. As a very special case, the Government of India allowed the registration of the sale of the house a few months later. Jinnah was informed about this and according to the high commissioner, instead of getting a thank you note, he got a brusque answer saying that he was glad that the right thing was done which should really have been done long ago.

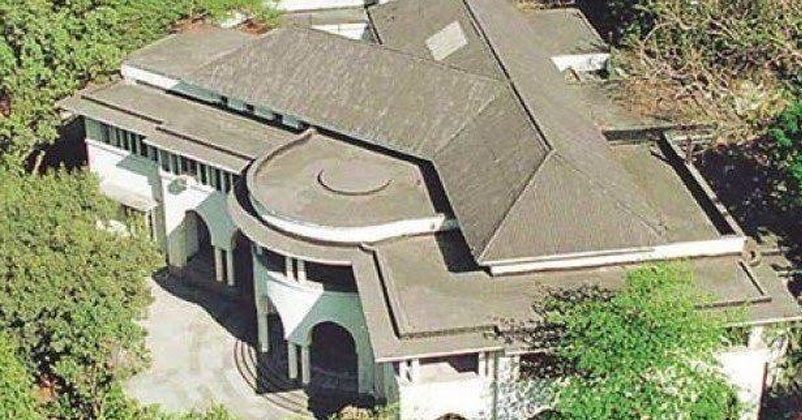

Jinnah was also attached to his house in Karachi and concerned about finding a suitable tenant.

On 17 March 1948, Jinnah and his sister invited the newly arrived American ambassador to Pakistan, Paul H. Alling, for tea. After inquiring whether the ambassador was making progress in the acquisition of property, Jinnah and Fatima asked whether the ambassador would be interested in their house ‘flagstaff’. A few days earlier Fatima had told Alling that it would be available for purchase. The ambassador replied that they were already negotiating the purchase of the ambassador's residence before they became aware that 'Flagstaff was available, and it would be impossible to withdraw from that negotiation. Jinnah then asked if 'Flagstaff' could be suitable for other personnel of the embassy. The ambassador had to regret again saying that they would not be able to justify the purchase of such a large property for any subordinate personnel. The ambassador sensed that Jinnah and his sister were disappointed that the Americans had not been able to purchase 'Flagstaff'. On receiving the details of the ambassador's meeting with Jinnah, a thoughtful secretary of state called the American embassy in Karachi to present to Jinnah four twelve-inch oscillating fans with the compliments of the United States.

At the dinner reception that Jinnah hosted on 14 August 1947, Lt Col (later Maj. General) Akbar Khan expressed his disappointment that higher posts in the armed forces continued to be held by British officers. Jinnah, retorted, ‘never forget that you are the servants of the state. You do not make policy. It is we, the people’s representatives who decide how the country is to be run. Your job is only to obey the decision of your civilian masters. Present-day civilian leaders would do well to recall this incident in their dealings with the army.

Jinnah’s love for his own properties was in sharp contrast to the treatment he meted out to Shivrattan Mohatta whose Mohatta Palace in Karachi was requisitioned by Pakistan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1947. When he managed to meet Jinnah at a state function for Karachi businessmen, he interceded for his house. He received no sympathy. 'It is a matter of state,' Jinnah simply said before walking off, unmindful of the fact that his properties in India too were “matters of state”.